Foreword

Susan Pevensie (Anna Popplewell), demon archer. From the film version of “Prince Caspian”.

Susan. Such a comfortingly old-school name. You couldn’t move for Susans in the UK sixty or seventy years ago, which is why the name was such a popular choice for British authors of that era - Susan Walker from Swallows And Amazons, Susan Foreman in television’s Doctor Who, as well as two of the best in C.S. Lewis’s Susan Pevensie and Alan Garner’s Susan, although the latter may well have had the Lewis character in mind.

And it is hard to imagine that Terry Pratchett’s choice of the name for the magnificant Susan Sto Helit, teacher, aristocrat and Death’s grand-daughter, was an accident, given this fine tradition.

We will return to Susan Sto Helit another day, make no mistake. But this post is about the two Susans from a previous era.

The Problem Of Narnia’s Susan

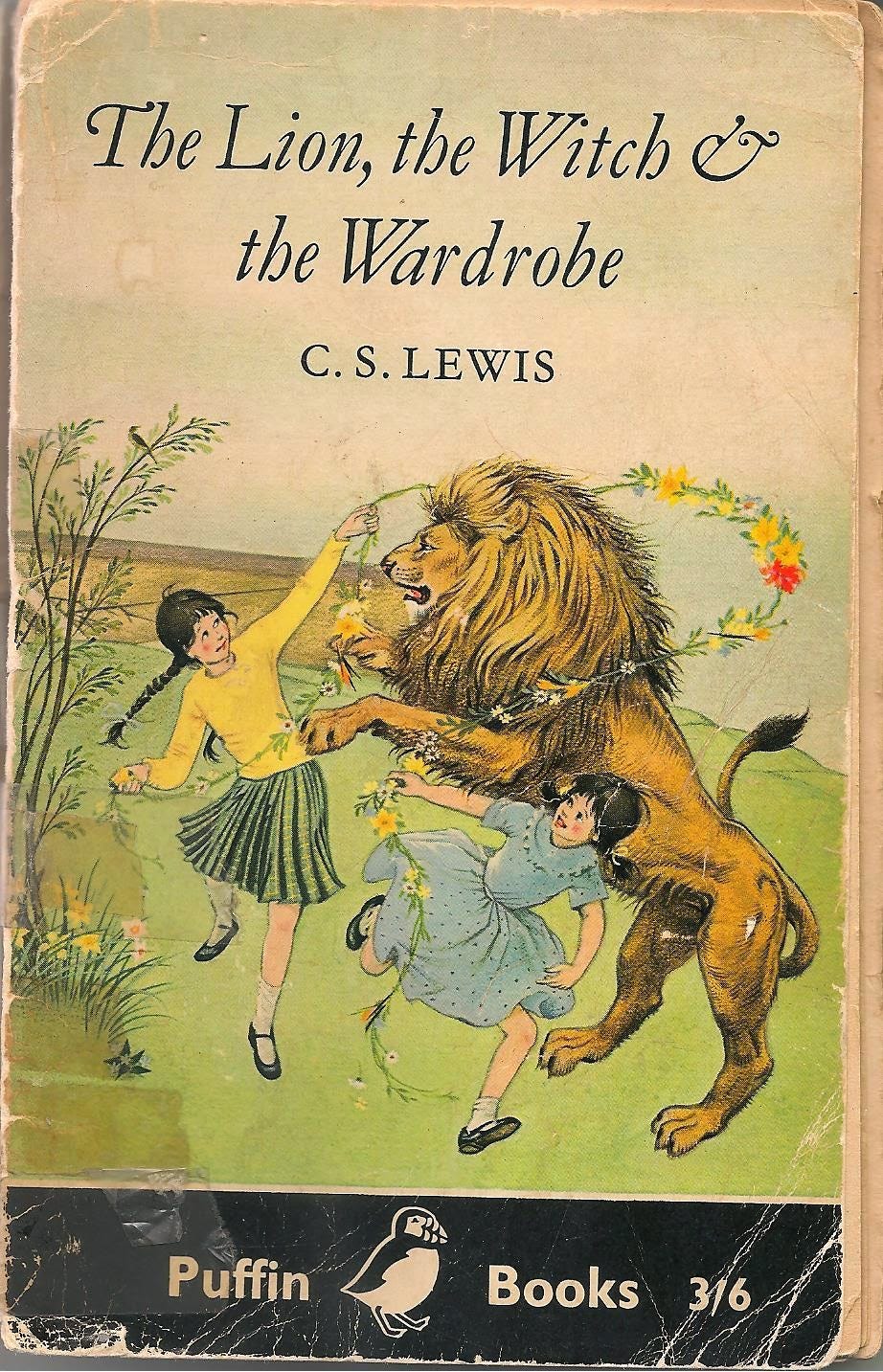

I’ve loved C.S. Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles ever since I was at primary school in the late 60s and I won a prize.

I forget what it was for, but I got to pick a book - to keep! - from the school library, which felt very important.

We’d been listening to the teacher read some of The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe and we were about halfway through, so I chose that, because I was desperate to find out how it ended.

L-R: Susan Pevensie, Jesus Christ in the form of a talking Lion, Lucy Pevensie.

The adventures of Lucy and her brothers, and elder sister Susan, in this land of talking animals and magic that you could get to through the back of a wardrobe, blew my seven-year-old mind and I was hooked. On the fantasy genre, too, although I didn’t know that phrase just yet.

Over the next year or two I read the whole series. I still have copies of The Horse And His Boy and The Voyage Of The Dawn Treader that technically belong to West Norwood Public Library. When they have an amnesty I’ll send them back1.

By the time I got to The Last Battle I was at the grand old age of nine, and a little bit more world-wise.

I should say at this point that any criticisms I have of aspects of C.S. Lewis’ books should be taken on the understanding that they are written with love from the point of view of a lifelong fan.

It’s not that I misliked religion back then, far from it. I was a good little Catholic boy. I was even an altar-server (every bit as glamorous as it’s cracked up to be, by the way).

Its just that I didn’t want it impinging on my entertainment activities. Church and Play should remain separate.

Lewis really dials up the muscular Christianity in The Last Battle as Aslan piously and brutally ends that lovely magical world for ever, for no apparent reason other than to complete his religious allegory. Oh, and the kids all die in a train crash.

But at least they all go to heaven, right? Right?

Wrong. Not all of them. Susan was brutally written out of the story. In a final twist of the knife, she doesn’t even appear in that final book because Lewis wants his Message to get through about What Happens to Bad Children who Stop Believing. And all the other kids join in the bitch-fest.

“Sire,” said Tirian, when he had greeted all these. “If I have read the chronicle aright, there should be another. Has not your Majesty two sisters? Where is Queen Susan?”

“My sister Susan,” answered Peter shortly and gravely, “is no longer a friend of Narnia.”

“Yes,” said Eustace, “and whenever you’ve tried to get her to come and talk about Narnia or do anything about Narnia, she says ‘What wonderful memories you have! Fancy your still thinking about all those funny games we used to play when we were children.’”

“Oh Susan!” said Jill, “she’s interested in nothing now-a-days except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.”

“Grown-up, indeed,” said the Lady Polly. “I wish she would grow up. She wasted all her school time wanting to be the age she is now, and she’ll waste all the rest of her life trying to stay that age. Her whole idea is to race on to the silliest time of one’s life as quick as she can and then stop there as long as she can.”

I was devastated by this, in particular the rest of them ganging up on her. I thought of how she must have felt, all alone in the world.

I still love the books and re-read them regularly, but it isn’t quite the same.

It seems that I’m not the only person to feel like this.

Neil Gaiman wrote a short story called The Problem Of Susan which is available in full here, in which a thinly-disguised Susan (Hastings, not Pevensie), living alone, a middle-aged professor of English, specialising in Children’s Literature, is being interviewed about a traumatic event in her life which mirrors that of the Susan in the books.

Greta can feel herself blushing, and she says, “It’s just I remember that sequence so vividly. In The Last Battle. Where you learn there was a train crash on the way back to school, and everyone was killed. Except for Susan, of course.”

The professor says, “More tea, dear?” and Greta knows that she should leave the subject, but she says, “You know, that used to make me so angry.”

“What did, dear?”

“Susan. All the other kids go off to Paradise, and Susan can’t go. She’s no longer a friend of Narnia because she’s too fond of lipsticks and nylons and invitations to parties.”

…

The professor cuts herself a slice of chocolate cake. She seems to be remembering And then she says, “I doubt there was much opportunity for nylons and lipsticks after her family was killed. There certainly wasn’t for me. A little money, less than one might imagine, from her parents’ estate, to lodge and feed her. No luxuries …”

“There must have been something else wrong with Susan,” says the young journalist, “something they didn’t tell us. Otherwise she wouldn’t have been damned like that, denied the Heaven of further up and further in. I mean, all the people she had ever cared for had gone on to their reward, in a world of magic and waterfalls and joy. And she was left behind.”

“I don’t know about the girl in the books,” says the professor, “but remaining behind would also have meant that she was available to identify her brothers’ and her little sister’s bodies. There were a lot of people dead in that crash. I was taken to a nearby school, it was the first day of term, and they had taken the bodies there. My older brother looked okay. Like he was asleep. The other two were a bit messier.”

…

It should be remembered that in the books, Susan, along with Peter, Edmund and Lucy, lived in Narnia for ten to fifteen years, maybe more, growing to adulthood and ruling over a kingdom. We see the adult Queen Susan in The Horse And His Boy along with Queen Lucy and King Edmund (who they obviously defer to as the oldest male present), and then again at the end of The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe.

At which point they forget about their “first adulthood” when they come back through the wardrobe as children again.

But … those life events still happened to them. The physical changes they went through still happened to them. Puberty still happened to them.

And what would the effects be of those memories, locked away in the brain of a child/woman, in particular to a child going through second puberty?

I think the only thing Gaiman got wrong was that he understated the level of horror Susan would have experienced.

The Mystery Of Garner’s Susan

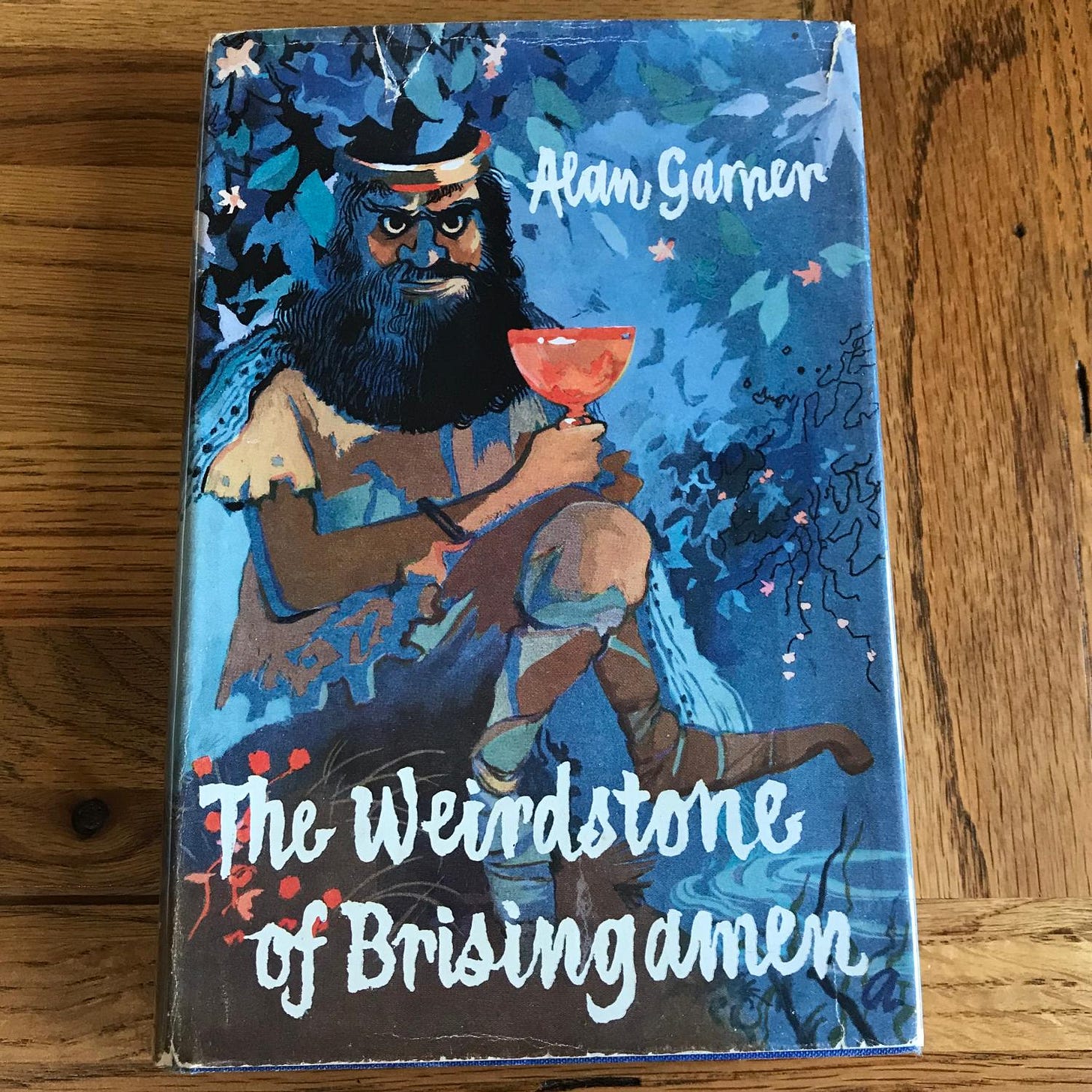

The terrifying original cover to Alan Garner’s classic “The Weirdstone Of Brisingamen”

The other Susan in this article, the one we meet in Alan Garner’s books, has a better end to her story - I think…

We first meet Susan and her younger brother Colin in The Weirdstone Of Brisingamen. In their ensuing adventures, it is generally Susan, the smarter and more mature one, who gets Colin through, particularly in the sequence everyone rememebers where the children find themselves underground and have to find their way out, in a brilliantly-written, claustrophobic chapter.

During The Moon Of Gomrath, a more mature Susan shows signs of restlessness and change, and at the end, suddenly leaves her brother, with no warning and of her own free will, and seems to travel to somewhere not on this Earth.

And there the story pauses, and is not taken up again by the author for almost fifty years.

When we do meet Colin again, in Boneland, he is Professor Colin Whisterfield, a genius-level astronomer working at Jodrell Bank, observing and listening to the stars, driven by an obsession to find out what happened to the sister he cannot remember, only the unbearable sense of losing her, and the conviction that he will find her if only he studies the far-off Pleiades star cluster.

The lack of continuity is as jarring for the reader as it is for Colin, who at the outset of Boneland has spent the past 30-40 years on his fruitless search, despite having no memory of the events of the first two books, or indeed of anything else before he was thirteen years old. Strangely drawn to Alderley Edge, he lives on his own in a nearby cabin situated in a quarry, miles away from anywhere.

Although Susan’s presence hangs over events throughout the book, she is never named (because Colin can’t remember her name) and is only heard by Colin, briefly, a couple of times - early on , at the Jodrell Bank visitors’ centre in a “whispering gallery” created between two dishes set forty metres apart to demonstrate how sound can carry, then again towards the end - but she is definitely OK, wherever she is.

Full disclosure here. I’ve read Boneland three times, once in a print book, once on Kindle and once on audio, and I still don’t know exactly what happens. Not just at the end. All the way through.

I’ve looked at reviews of the book, and there are plenty of smart people, Neil Gaiman for one, who don’t know either, and freely admit it, and there’s others who think they have an explanation but it doesn’t really add up.

So I’m not really qualified to say how it ends for certain. But Susan is OK. She’s OK.

Epilogue

I guess the takeaway is, if you're a Susan in a book, best hope you're written by Alan Garner, not C.S. Lewis.

Susan Pevensie is treated a lot better in the big-screen Chronicles Of Narnia, being given a romantic sub-plot with Caspian (never mind the thousand-year age difference).

The Weirdstone books have never been adapted for the big screen or even the small screen. I think some huge changes and expansions to that world would need to be made, which maybe Alan Garner is not prepared to allow.

The only way it would work properly would be if Garner himself was involved, as he did when he wrote the screenplay for The Owl Service - and I think the time may have passed for that, which is a shame.

Other articles you may enjoy:

Worth A Read #1 - "I Capture The Castle" by Dodie Smith

I will never take them back. Post-COVID, they’d only burn them so they’re better off where they are. Buried somewhere in the garage.

I loved Narnia, too... Read them all over and over, though I never stopped being devastated by The Last Battle and hence revisited it less frequently than the others. I've never heard of Alan Garner, though! After reading your piece, I'm intrigued and want to check them out (possibly from the library, albeit on a less permanent basis!).